| |

MEY

The Mey is a cylindrical double-reed aerophone used in Turkish folk music. Cylindrical in

shape and made of wood, it has 7 finger holes on its front side, and one finger

hole at the back. A double reed (kamish) is used that obtains the characteristic

sound of the instrument. A tuning-bridle called "kiskach"

serves to tune the Mey and to prevent alterations in pitch of the sound. A wooden piece smilar to "kiskach"

which is called "agizlik" covers the part of the reed's mouth, when the mey is not used

in order to preserve it. The size and nature of the reed is dependent on the size and nature of the

instrument.

|

|

Photo: courtesy of Oliver Seeler / Nova Albion Research |

|

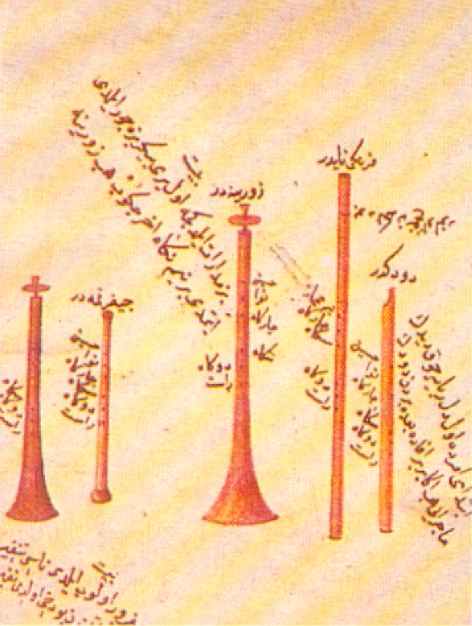

94. Auloi (a pair of Aulos) (Greece,4th centuryB.C.);

95. Kuan (China); 96. Guan (Mongolia);

97. Ana Mey(Turkey);

98. Nerme Nay (Iran); 99. Duduk (Armenia)

|

There are many instruments similar to the Mey in Asia. These are called "Balaban", in Azerbaijan, Iran and Uzbekistan; "Yasti Balaban" in Dagestan;

"Duduki" in Georgia; "Duduk" in Armenia; "Hichiriki" in Japan; "Hyanpiri" in Korea; "Guanzi" in China; and "Kamis Sirnay " in Kyrgyzstan.

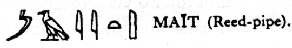

Musicologists like Farmer (1936: 316) and Picken (1975: 480) have suggested

that ancient Mait, Monaulos, and Auloi present major resemblances with the Mey and the other

similar instruments. In Hellenistic Egypt, there was an instrument called "Mait"

or "Monaulos" which was similar to the Mey and there was another one in Anatolia

which was called "Auloi" and its picture was found on a vase.

In the written history of Turkish music, the oldest Turkish source regarding

the Mey is a work that dates back to the late 14th or early 15th century titled

"Makasidül-Elhan" written by Maragali Abdülkadir (ABD AL-QaDIR [ibn Ghaybi

al-maraghi]) (1350?-1435) who was a composer, performer and theorist and

traditionally considered to be the founder of Turkish music research. In this

work, the instrument referred to as "Nayçe-i Balaban" is likened to the "surnay"

which is another name of the "Zurna" and its soft and wistful sound (Bardakçi1986: 107).

|

Evliya Çelebi (1611-1683), who lived two centuries after Abdülkadir, has

described this instrument in the following manner. He said, "The Belban (or

balaban, reed pipe of the Turkmens) was invented in Shiraz. It had no "kalak" (the

enlarging mouth of the instrument) resembling that of zurna which is double reed

Shawm. It was used mostly by Turks and there were about a hundred players in

Istanbul" (Çelebi 1314: 61). At the end of the eighteenth century, among the

instruments used in Egypt, which was then located within the borders of Ottoman

Empire, there was a detailed drawing of an instrument, closely resembling the Mey and called "irakiyye", in Aksoy's book "Music in Ottoman Empire" (Aksoy

1994:282).

The actual names "Mey" and "Balaban" are the modified forms of the term's

"nay-i balaban" or "nayçe-i balaban" which were altered through time. The suffix

"-çe" is the diminutive suffix and "nay" means reed in old Persian and so, "nayçe"

means "small reed". In some collections, we also encounter the term Mey used

alternately with the term Nay. Laurence Picken also gives it the name "mey or

nay" when he introduces this instrument in the "Folk Musical Instruments of Turkey".

He writes that "...the mey bodies which are manufactured for the Erzurum market are called nay" (Picken 1975: 475-477). As a matter of fact, another name for

"duduk" which is used in Armenia, is Nay. (Haygayan Sovedagan Sosyalistagan

Hanrakidaran.1977.Volume 3:459).

|

Ney |

|

Mey |

The word Nay, when modified according to the phonetics of Turkish, becomes ney, not to be confused with the reed flute "Ney" of Turkish classical music.

Therefore, most probably, the name mey is given to this instrument in order to

distinguish these two instruments.

Cevri Altintas used the Mey for the first time in 1950, during, a broadcast

on Turkish State Radio. Later, it was included in Turkish folk musical groups

and is in wide use today. Currently, because of the effects of mass

communication, the increase in the number of institutions where music education

takes place, and particularly due to the realization of the meaning and

importance of professional performance, the Mey has become widely used in almost

all parts of the country.

S. Y. Ataman

with C. Altintas's Mey |

This popularity has certainly caused some changes. In the 1950s, the Mey was used in just a few folk music compositions, because players used an instrument with

a range of only one octave. During the first years when the Mey was played on

Turkish State Radio, a folk song followed a solo mey performance. The performer

only had a single mey in hand and thus tuning was impossible. Later, this

problem was solved with various sizes of mey(1) . Ataman, the folk music

researcher, (1906-1994) confirmed this situation and exhibited Cevri Altintas's

mey which was in his collection.

|

Meys in different sizes

|

|

In initial studies, according to the information and drawings in their

books, the composer and musicologist Saygun (1937: 50), and musicologists

Ülgen (1944: 36) and, Gazimihal (1975: 74) mentioned that before the

modification process, the mey had a total of 9 finger holes, 8 on the

front and one at the back, but later studies did not verify this

information. It is, however, interesting that similar instruments played

in neighboring countries have 9 finger holes. According to my own findings

and those in the literature, the size of the mey is approximately 30 cm.

After the modification process in 1961, according to the information

obtained from Binali Selman, a famous mey player, three sizes of mey were

being played: ana (the largest size), orta (middle), and cura (the

smallest) (Picken, 1975:476) This classification has been valid for many

years. Until the 1990s, these three sizes of mey have been used and by

means of the reed and bogaz "adaptor," one tries to solve the problem of

tuning the mey with other instruments. In the resulting heavy demand,

Ayhan Kahraman, the manufacturer of the instruments, produces 8 separate

sizes of mey each corresponding to a diatonic sound. A Tonic in the

Instrument corresponds to each sound of the piano. In this Turkish folk

instrument in which the possibility of transposition is limited, it is

necessary to change the mey whenever the key changes.

The mey is found widely in the eastern region of Turkey (2). Here, this

instrument, however, it is no longer used in some provinces and in same cases is

played in other provinces (3).

The structure of the mey is most suitable for the character of

the music of the East Anatolia. It has a non-strident sound, and for this reason, it is preferred for

indoor use. Most of the Mey players in Turkey can also play the Zurna. They

usually have a lower social status and most of them are wedding musicians. The

social status of the players, however, has been somewhat improved.

The role played by the Zurna in outdoor is carried out by the Mey indoor.

The "Def" or sometimes a second Mey generally accompanies it.

While one of the Meys plays the tune "ezgi", the other sustains a drone called

"dem". It takes the place of an accompanying instrument when played by groups;

and used to play before the tunes, "taksim" improvisation which is also called "yol gösterme",

"gezinti", or "açis". Its mellow and wistful sound is consistent with these

forms. It has also been used as a minstrel's instrument, or "ashik sazi". We can

observe a typical example of this in Aga Keskin who is a mey player (4). The

artist first plays the mey, and then sings the song while the mey is silent; he then takes

the mey again to continue the tune.

Because the range of the instrument is limited to one octave in order to play

a scale, sounds are produced by means of the fingers and lips and only certain

modes (makams) may be played (5).

HOW TO PLAY THE MEY

When playing the mey, the left hand should be above and right hand below the

instrument. The little finger of the left hand and the thumb of the right hand

are not used. Continuous vibrato is heard when playing due to the use of a big

reed. When the player wants more vibrato, however, he either vibrates his jaw

with rapid intervals or shakes the instrument with both hands. One of the most

important things a mey player should achieve is to play the tune continuously,

which necessitates circular breathing.

STRUCTURE OF THE MEY

The body of a mey is generally made of plum wood. Although the preferred wood

is from the plum tree, other trees such as walnut, mulberry, beech, apricot,

acacia, olive, and rose are also used. Recently, wood imported from Africa is

also used.

The top opening of the mey where the reed is inserted, is twice the size of

the bottom. The diameter of this opening is between 10 and 20 mm. in the largest

size of the mey. It is from 10 to 18 mm. in the smallest mey. A large reed is

used for a large sized mey, and small reed is for the small sized mey. If the

drone is not sustained, a disturbance occurs in the sound. The finger holes are

in equal distance from each other and their diameter is 6 mm. in all sizes of

meys.

Mey body production |

When we inquire about the master craftsmen who make their meys

themselves in Anatolia. Even if some masters manufacture their

instruments, very few of them earn their livelihood in this way. Among

these masters (usta), the oldest and best-known was Dikran Nisan of

Diyarbakir who was called Niso Usta (6). The other masters, who used to

make meys in Anatolia, were Master Tosun in Pasinler and Master Hakki in

the Erzurum province. These two masters managed to be manufacturers of

meys besides being carpenters. (Isikli, 1992). The mey player who is

called Cabbar, in the province of Artvin, manufactures it with a

manual-lathe similar to the master craftsmen mentioned above.

Today, primarily in Istanbul, the manufacture of the meys and zurnas

has become a thriving business. There are 4 manufacturers who produce the

instruments These include the master craftsmen Hasan An in Tahtakale,

Aydin Konuk in Edirnekapi, Ali Riza Acar in Esenler, and Ayhan Kahraman in

Ümraniye. They all use electric lathes, but the only one among them who

exhibits quality work is Ayhan Kahraman who has produced instruments since

1980, and plays the mey and the zurna quite well. He continuously improves

manufacturing techniques for his instrument and uses good quality

materials (7).

|

Reed (kamish) production

|

The mey reed are made from fresh water reeds, their length varying

approximately between 80 mm. to 150 mm., the mouth of the reed between 20

mm. and 40 mm. The sound characteristic of the mey is obtained by its long

and large reed. One end of the reed, which is cut through its joint

(knot), is flattened to fit into the players' mouth. The other end is left

round as is the original shape of the reed. This end is inserted into the

head - part of the mey which is enlarged for the reed. The reed is left

thick in the part to be inserted into the mey, or it is made airtight with

waxed threads. Some modifications appear in mey bodies as well as in the

reed structure. In the reed structure, in the past, the reeds were used by

making a knot with threads in a place near the lower region (Isikli,1992).

The reed manufacturer Sehamettin Tekin has confirmed this (Tekin 1992).

The researcher Cemil Demirsipahi has drawn pictures of mey reeds with

tuning - bridle (Kiskaç) and with thread (Demirsipahi 1975 194). Another

interesting finding is that the aulos and monaulos reeds belonging to the

Hellenistic period of Egypt were with joints (knots).

The tuning - bridle (kiskaç) which is mounted on the mey reed is made

of a wood piece, and is bound on both sides. It not only makes the playing

of the mey comfortable but also is used for the adjustment of the sound

tone and tuning. Until recently, their players made their own reeds, as

well as their instruments. With changing living conditions and the

increase in the number of players, some of them have turned to the

manufacture of reeds. The oldest known reed manufacturer is Sehamettin

Tekin who is now too old to produce reeds. Tekin has stated that he

learned how to make reeds from Aga Tastan, and that the reed shapes in use

nowadays owe their popularity to his school of reed production. (Tekin

1992). Currently, Mehmet Simsek and Dursun Kement in Istanbul and Ali

Zeynel Çiftçi in the Hatay are making reeds.

THE MODIFICATION PROCESS OF THE MEY

As a graduate of the Turkish State Conservatory of Music in Istanbul, I was

schooled in both Western and Turkish traditional musical systems. As a result of

this bimusical background, I play Western flute as well as the mey. The

familiarity with the flute performance practice inspired me to explore the

possibilities of modifying the mey in order to overcome its technical

limitations which have led to problems in executing specific intervals,

transposition, and modulation.

I sought to achieve these goals by working with an instrument maker in

Istanbul who was open to experimenting with methods of extending the range of

the instrument and changing the nature of the large double reed. Attempts to

accommodate more scales by manipulating the reed proved to be unsuccessful as

the unique mellow sound of the instrument would be altered significantly.

Despite this success in producing a new and evolved mey, and the ability of

instrument to perform a full range of folk music repertoire, there has been some

resistance from traditional folk musicians.

There have been no significant changes in the physical structure of the

mey. Only its present state has been adjusted to current conditions. I

tried to improve the structure of the mey, and while realizing this, I

tried not to spoil its unique sound. My aim was to improve the sound and

the range of the mey. First, I tried to obtain an octave or five tones

from the same sound hole, similar to over-blowing a flute or clarinet.

Because the reed, however, is double-sided and large, this was not

possible. It was necessary to change the structure of the reed, and this

would spoil the original sound of the instrument. Second, I tried to

obtain a larger range by drilling holes in the reed, to extend the

fingering but this was not possible. Later, by placing keys on the body of

the instrument it was possible to increase the range by an octave and a

forth and to produce semitones and microtonal pitches.

|

|